For the December 2014 segment of Righting Crime

Fiction, I will continue talking about how you can use firearms evidence to

solve your fictional crimes that involve guns, with a focus on spent shell

casings and the link between casings and firearms.

FIRING PIN FINGERPRINTS

A bullet casing can be scarred in a number of

ways upon being fired and ejected from a firearm, but the most beneficial and

telling “scar” would be from the firing pin. When a firing pin strikes the

primer (on centerfire bullets) or the rim (on rimfire bullets), it leaves a

unique mark similar to a fingerprint. What happens is this: the firing pin

strikes every bullet it fires in the same way each and every time (unless there

is damage or some other change to the weapon), which leaves the exact same

imprint each and every time. This “fingerprint” left by the firing pin is

extremely helpful in determining if a particular firearm fired a particular bullet

casing.

CENTERFIRE VERSUS RIMFIRE

What’s the difference between centerfire and

rimfire? Quite simply, the firing pin on a centerfire weapon will strike the

center of the casing’s head (the primer), while the firing pin on a rimfire

weapon will strike the rim of the casing’s head (where the priming compound is

located). Most modern firearms are of the centerfire variety. However, there

are still numerous rimfire weapons available, many of which fire the very

popular .22 caliber bullet.

Plinkerton

.22 Caliber Single-Action Revolver

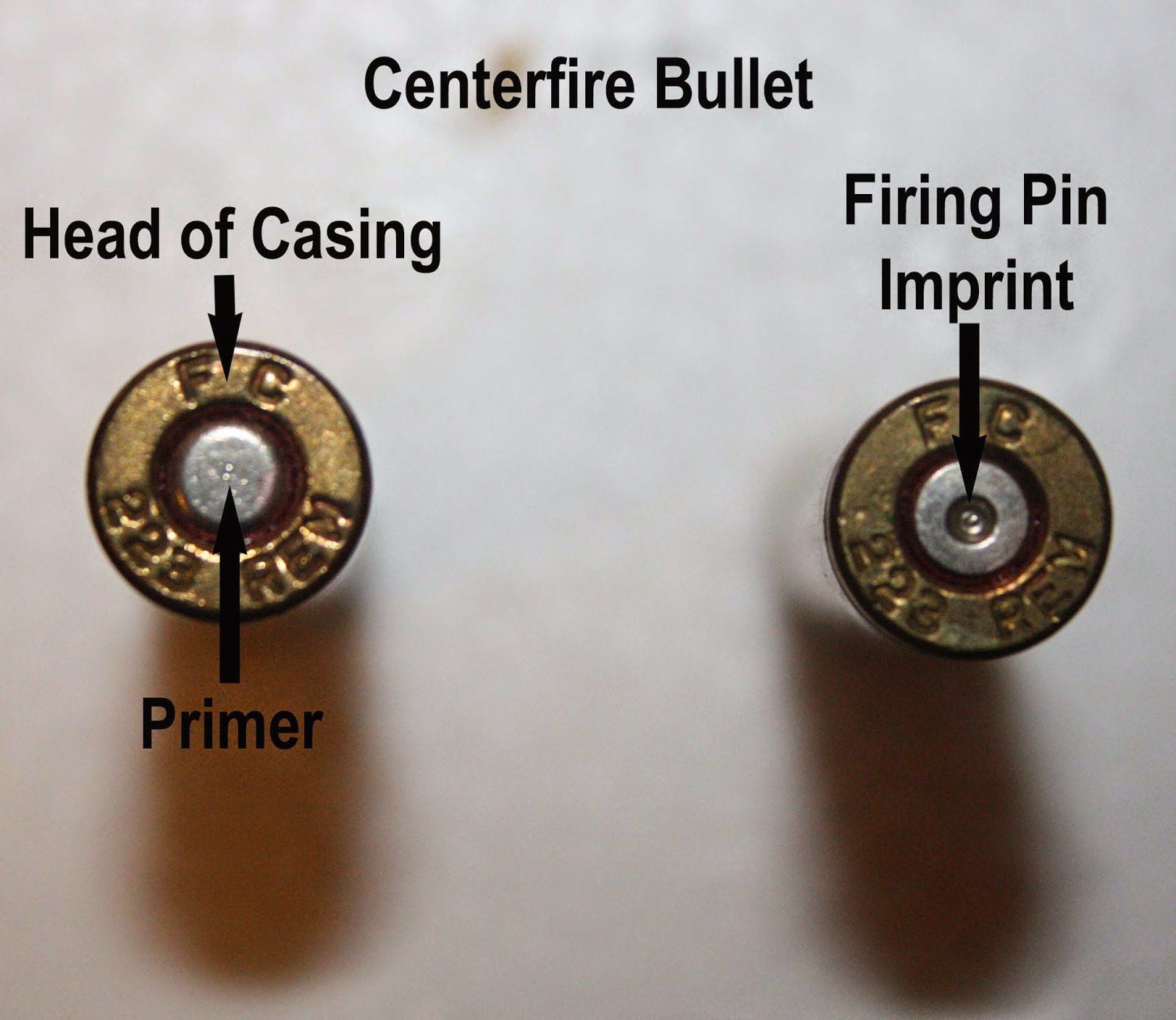

NOTE: The following two photographs demonstrate the

difference between a centerfire bullet and a rimfire bullet. In both photographs,

the unfired bullet is to the left and the spent shell casing is to the right.

Centerfire

Bullet/Casing

Rimfire

Bullet/Casing

LINKING THE SCENE TO THE GUN

If your detective only has spent casings in her

possession and no firearm to which she can compare them, the casings are nearly

useless. (They might make for a cool-looking necklace, but, other than the

benefits previously described in the November segment regarding caliber

identification, etc., they won’t help her solve her case.) Of course, there are

at least two ways to use the lone shell casings without an accompanying firearm

(I will discuss one in a later post and the other at the end of this section),

but in most cases it is imperative that she recover the firearm used in the commission

of the crime. In real criminal cases, we have to work with what we have and

there are many times when we are unable to recover the firearms used in the

crime. However, you control your fictional world and you can work out creative

ways for your detective to recover the firearm—unless it suits your story to

keep the firearm hidden.

With the casings and the firearm in her

possession, your detective is now ready to attempt to have the two linked together.

The first thing she would do is submit the spent casings and the firearm to the

lab. Once at the lab, these items may be processed for other evidence (DNA,

fingerprints, etc.) before the ballistics examination begins. When these other tasks

are completed, the firearms examiner can begin comparing the spent casings to

the firearm.

The examination is not carried out by directly

comparing the spent casings recovered at the scene to the suspected firearm.

Instead, the firearms examiner will compare the spent casings recovered at the

scene to a “known” spent casing fired from the firearm. In order to obtain this

“known” casing, the firearms examiner would test fire the firearm under

controlled conditions (usually by firing into a large water tank located at the

crime lab), and then compare the firing pin marks on the recovered shell

casings to the firing pin mark on the “known” casing by viewing them

side-by-side under a microscope. If these marks are the same, the firearms

examiner can conclude that the casings were fired from the same firearm. In

addition to these firing pin marks, or “fingerprints”, the examiner will search

for other unique “scars” left on the spent casings, such as the ejector or

extractor marks. These additional marks will aid the examiner in bolstering his

conclusion that the spent casings located at the crime scene were fired from

the firearm in question.

Now, when your detective links a spent shell

casing she recovered from a crime scene to a particular firearm, she has linked

the crime scene to that weapon. She must then link the firearm to the suspect,

and I will discuss that in a future post.

WHAT IF MY DETECTIVE DOES NOT HAVE A FIREARM?

If your detective does not have the suspected firearm

in her possession—as mentioned earlier—the casings are nearly useless. However,

certain casings can be entered into a database called IBIS (Integrated

Ballistics Identification System)/NIBIN (National Integrated Ballistic

Information Network), where they would be compared against other casings

recovered in connection with other crimes around the country. If the system

identifies two casings that are similar, a firearms examiner would then compare

the two to make a final determination. Now, this would indeed be a long shot,

and you should seek out more creative ways (I’ll discuss one in a future post) to

have your fictional detective link the casings to a particular firearm.

TRANSFERRING TO FICTION

Unless you are writing your story from the point

of view of a firearm’s examiner, you only need a very basic knowledge of the

examinations process, as described above. As a detective, I simply recovered my

evidence in the proper manner and submitted it to the crime lab utilizing

acceptable procedures (also to be discussed in a future post), and then I would

sit back and wait (doing other things on the same case or working new cases, of

course, but my work was done for the moment as far as that evidence was

concerned). I would later receive a report from the lab detailing their conclusions.

If more information was needed, I’d simply call the examiner and discuss his or

her findings.

In the following example from one of the first

short stories I ever wrote (A COLD MURDER, Detective

Mystery Stories Magazine, February 2004), the firearms examination takes

place off-page and the results are communicated in dialogue:

Cade

knelt outside the driver’s door of the truck and looked under the seat. There

was a Burger King bag and a couple of compact discs. He pulled the bag out and

something rolled across the floorboard and came to rest under the brake pedal.

He felt for the small object and, when his fingers found it, he knew instantly

what it was—a nine-millimeter shell casing.

“Les,

stand in front of the truck,” he said, excitement starting to course through

his veins. He stood outside the open driver’s door and pointed his finger at

Leslie. “If I’m shooting at you, my casings are gonna eject to the right and

back. Most of the casings will ricochet off the side of the truck and fall to

the ground, where we found them. But one—that missing one—found its way into

the truck. I’ll bet my left foot this is the casing that we couldn’t find at

the scene.”

Leslie

kept the Cassells preoccupied while Cade raced to the crime lab. He stopped

first at the firearm examiner’s office and then hurried down the hall to the

fingerprint lab. Within the hour he was back at the station house with the

results.

When

he and Leslie were seated in his office with Joseph Cassell, he held up the

casing and said, “You see this?”

Joseph

nodded.

“This

was found under the driver’s seat in your truck.”

“I

have lots of fired casings around the house and in my truck. When I go deer

hunting I usually throw my empties in the back of my truck. I clean them up

later. I must’ve missed that one.”

“You

hunt deer with a pistol?”

“No.

I have a nine millimeter carbine that I use.”

“Well,

this is a special casing.” Cade set it on the desk in front of Joseph. “This

casing matches four other casings that were found at the scene of Jeffery

Stokes’ murder. And that’s not all. We found Jeffery Stokes’ fingerprints on

the hood of your truck.”

Joseph

started in his chair. “Are you saying I did this?”

“If

you did, I wouldn’t blame you much. Had I just learned some sick pervert was

taking nude photos of my daughter—”

I’ve also worked actual cases

where the firearms examiner processed the evidence as I waited, and I detailed

such a scene in another of my early short stories titled A BADGE LIKE MINE (The Writer’s Hood, October 2003):

I drove to the crime lab and gave Willie

the chrome pistol. “Check this against the bullets from the Wilson murder . . .

I’ll wait.”

“Oh,

you want it done now?” Willie asked.

“Please.

It’s kind of important.”

Willie

took the pistol and fired it into a large water tank. The casing ejected from

the pistol and bounced off the wall and rolled under the tank. Willie fished

the projectile out the tank and asked me to get the casing from underneath. “My

back ain’t what it used to be,” he said.

I

had to use a broom to get it out and then handed it to Willie. He marked it and

then stabbed it onto a piece of clay opposite the casing that was recovered in

the Wilson murder. Muttering to himself, he hunched over his microscope and

turned this knob just so, adjusted that one a little, moved the casing ever so

slightly . . .

“Yep,”

he finally said. “This is a match.”

So, it’s as simple as that. You can have your

firearms examiner come to the conclusion that will move your story in the

direction you want it to go. Bear in

mind, though, that in the majority of real cases, firearms evidence will take

days, weeks, or even months to be processed at the lab, especially if

submitting to a state crime lab with a heavy workload. However, if you need

ballistics evidence to come in quickly for the sake of your story, that is also

realistic. I worked several murder cases where time was of grave importance and

the firearms examiner processed the evidence on the spot while I waited.

Well, that’s all for the December post, folks. I

wish all of you a happy, healthy and prosperous New Year filled with lots of

writing success.

Until then, write, rewrite, and get it right!

©BJ Bourg 2014